I recently had the pleasure of attending a press preview of the new documentary Architecton, directed by Victor Kossakovsky and released last week by A24.

Surreally, the screening I attended was held inside a Cedars-Sinai medical-imaging center in west Los Angeles. Seeing this particular film, with its intensely granular focus on the geological underpinnings of the built environment, amidst diagnostic tools designed for peering inside the human body seemed strangely appropriate.

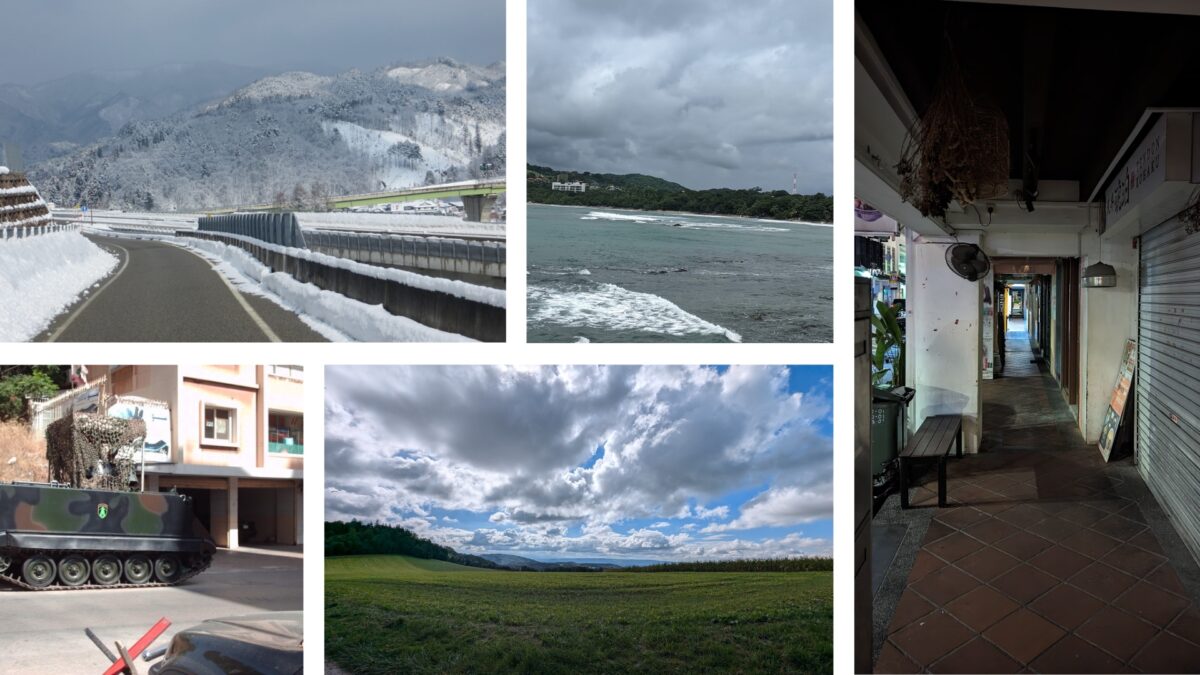

I imagine that, if you were simply to wander into a room where Architecton was playing, it would very likely appear to be a film about geology: about rocks and mountains, quarries and mines, and the raw streams of matter that create and emerge from them.

There is an extraordinary early sequence, for example, from which the stills in this post were taken, where Kossakovsky captures a landslide. We watch as increasingly large rocks, from sand to gravel to room-sized blocks to immense boulders, all flow downhill in slow motion, crashing into one another, exploding, ricocheting, and splitting apart.

It looks for all the world like an oceanic phenomenon—a series of waves, not a solid planet at all, as if the Earth has begun to boil and heave with liquefaction.

The sequence then fades into what I believe is an aerial drone shot of the same landslide, but the visuals here become almost astronomical in their power and beauty, as if Architecton had somehow captured a proto-planetary storm of partially aerosolized rock. It looks like you’ve woken up inside the asteroid belt—or perhaps what J.M.W. Turner would have depicted if he had traveled in space. Not landscapes but nebulae.

There is something so elemental, even infernal, in this sequence, verging on the cosmic: glimpsing how the Earth itself was assembled through a billion-year maelstrom of mineral hurricanes, spherical landslides, and weather systems made entirely of geology.

Later, the camera lingers over detonations in the walls of strip mines. We watch rocks being bounced and agitated on conveyor belts, wet with leachate and acid. At one point, the camera stares into a minimalist doorway, cut like an Etruscan tomb, through which rocks tumble to be processed as abyssal red embers glow.

It’s just a mine, of course, but Kassakovksy has made it look like an alchemical complex, a brutalist oven in which all things planetary can be melted and enhanced, sluiced off and purified, distilled into a purely economic form. It is brute oceanic metallurgy.

It’s these early sequences that I could have watched literally for hours. It was also these scenes that felt so perfect for the unlikely setting in which the film was being screened that day, knowing that, as we all sat there, people in the rooms around me were getting CT scans, MRIs, and X-rays.

But the movie takes a more architectural turn here, increasingly focused on buildings and cities, on archaeological sites and ruins. We see residential towers in Ukraine, for example, ripped open by Russian missiles and drone-bombs, and then earthquake-damaged apartments undergoing demolition and clearance, followed by landfill-dumping operations so large they look like attempts at terraforming.

These are intercut with the film’s only speaking sections, where we watch architect Michele De Lucchi supervise the construction of a small rock circle in his garden. A light snow falls and hazy mountains are visible in the background. The scenes are meditative and calming.

At one point, De Lucchi’s circle is visually rhymed with an all-too-brief aerial glimpse of what I believe is the Richat Structure in Mauritania, continuing the film’s play on form and organization, as if rocks have within them a natural capacity to resemble storms and hurricanes—as if everything we believe to be is solid is, in fact, made of vortices and waves.

And this is all perfectly enjoyable; I was mesmerized.

But the film ends on a strange note. Despite appearing—to me—to be a documentary about the Earth, geology, and elemental form—about the human relationship with matter and our attempts to control it—Architecton concludes with a somewhat head-spinning turn in which the director himself appears on screen and asks De Lucchi, in person, why humans now construct such ugly buildings.

The question felt totally out of the blue to me and, frankly, irrelevant to the rest of the documentary. Either I had mis-understood everything I’d seen leading up to that point or perhaps Kassakovksy had felt pressured to deliver some sort of easy takeaway, an interpretation or rhetorical question that critics could discuss after viewing.

Speaking only for myself, what I wanted to discuss as I walked out of the cinema was not whether we should build fewer glass towers in Milan, but whether or not we understand what the Earth really is; whether landslide dynamics repeat, in miniature, the formational mechanics of rocky planets in the early solar system; or whether our cultural—and, yes, architectural—encounters with rock, especially in the form of mines and quarries, might force us to reevaluate how we define humanism in the first place. Some people think literature makes us human, but what if it’s actually metallurgy?

In the end, it was as if someone had created a 100-minute-long Rorschach test, composed of extraordinarily beautiful imagery of landslides and rocks, only to spring out from behind a screen and tell us that, this whole time, he had been thinking about classical architecture.

Nevertheless, the film is worth checking out—and I’d recommend doing so in a theater while you can, for the sheer scale of what Kassakovksy depicts.

(Thank you to A24 for providing the stills that appear in this post.)